Debugging Your Brain Part 3, Experience Processing

This post was a precursor

to Casey's book

"Debugging Your Brain."

Experience Processing

Overview

Experience Processing

In this chapter “Experience Processing”, you will learn specific techniques to help you process experiences by putting them into words. Verbalizing an experience can help reduce the stress you feel about a given situation. It can help you feel more in control and at ease. It can help you express your experiences to others. It can help you choose the best response for the situation. You also get the opportunity to influence your future thoughts and feelings, through deliberate thought.

Putting the experience into words can be a huge relief, especially when the experience is complex or troublesome.

Words give us “handles” that we can use to inspect experiences. We can use these to investigate and figure out what’s really going on. By using accurate language, we can process experiences a lot more deeply and effectively than we can by using abstract wordless thoughts alone. You might verbalize an experience by thinking to yourself, by talking to a friend, or by writing.

We’ll cover six concrete techniques to help you process experiences more fully and effectively.

Automatic Inputs as Data

All of these techniques have one main overarching theme: “accept automatic thoughts and automatic emotions as inputs”. In the moment in which you experience an emotion, that emotion is already outside of your control and influence. In the systems model we described earlier (input, process, output), “you” are your conscious mind processing the experience, and these “automatic emotions” are inputs to your system. If you can accept automatic inputs as data, that will help you process them more fully. If you accidentally fixate on and judge these automatic inputs, that can be very counterproductive.

It can take a lot of practice and training to accept emotions as input. It will get easier with time and repetition. If you want to practice this deliberately, you might consider a meditation practice. Many meditation practices actively focus on observing thoughts and emotions non-judgmentally.

Avoiding Rumination

When processing thoughts and feelings, there is a risk of accidentally ruminating instead of effectively processing them.

Rumination is when you focus on the causes and consequences of something, instead of solutions. If you are too fixated on the negative, it may cause a downward spiral and make you feel even worse. If you notice yourself ruminating, you may want to take a break and try again later. If you’re not careful, you could accidentally reinforce maladaptive thought patterns.

With practice, you can develop techniques to effectively process experiences instead of ruminating on them. One technique is accepting inputs as things you cannot change. Another is identifying maladaptive thought patterns, and we’ll cover those in the next section.

Processing Experiences

Talk with a friend

Talking through an experience with a close friend is one of the most powerful processing techniques. This is also my personal favorite. Not only is it helpful for processing the experience, but it is also a bonding opportunity for the relationship.

You have to put your thoughts and feelings into concrete words in order to communicate them to another person. If your friend can accurately reflect back to you what you’re saying, that helps you be more confident that you are understandable. This confidence can help you feel more settled about that part of the experience. This can help you move on to processing other parts of the experience.

Sometimes a friend will describe something in a different way than you. If you like their phrasing, you might adopt it yourself. When you sometimes have trouble putting an idea into words, a friend can help you explore those. They might brainstorm different ways of describing it until something feels accurate and correct.

Here’s an example of how I process experiences with a friend.

- I ask the friend if they can help talk me through something. This makes sure they’re available to help me process my unprocessed thoughts before diving in.

- When sharing unprocessed thoughts, sometimes I end up rambling a bit. It can take a few tries to figure out the right word. For example, I might try: “I feel good about it. Excited maybe? Not quite excited. I do think it’ll go my way, and that’s a comforting feeling.”

- When I’m having trouble, my actively listening friend might suggest “are you feeling confident?“. If they’re right, we’ve named this feeling! If not, we can continue on until same description feels right. Often you can find a single word for something. If not, you can at least find a phrase or sentence-long explanation of the feeling.

If they can reflect back to you accurately how you’re feeling, that can make you feel understood by another person. It can be very comforting, validating your experience as understandable. This can help you feel like you can move on, now that the experience has been processed.

Talking with a friend is often the most powerful method of processing an experience, but talking with an unsupportive friend could make you feel worse. A friend might inadvertently invalidate your experiences, making you feel more uncertain about the experience. There are many tactics you can use to make your friends feel validated when listening to them, and we’ll cover those later in the book. If you can be a good model of active listening and effective validation, it may help your friends learn how to support you in a helpful way.

Rubber Duck

Not ready to talk to a friend? Try a rubber duck!

The “rubber duck debugging” technique is a common software development trick. Put a rubber duck on your desk, or imagine one. Pretend the duck is sentient and explain the situation to it. Imagine what questions it would ask, and what information it would need to know to be able to help. You could imagine the duck has the same context a coworker would have, or no context at all.

You can have a full-on conversation with this duck out loud, in your head, or in writing. By explaining the situation with words, you will understand it more clearly yourself, too. You may realize some assumptions you’re making, and be able to enunciate them. Often the root of the issue can be found within assumptions.

You can choose the identity of this imagined-audience to meet your needs - they could have similar context to a coworker, or someone else like your manager, your best friend, a family member, etc. And if you can’t think of an existing person who would be particularly appropriate, you can even imagine up someone new.

Duck vs Friend

Sometimes you may want to talk to a duck before a friend. The duck can help you think of what questions the friend would ask to get context, and what assumptions you’re making that would be helpful to make explicit.

The duck can help you “pre-process” your thoughts, putting it into words as much as you can on your own. By putting the experience into words, that helps you explain it more accurately, clearly, and succinctly. The more you can enunciate on your own, the smoother and deeper a discussion with a friend will go.

Often just by thinking through with a duck, I end up discovering exactly what I needed to know to figure out the situation. Often, I end up not even needing to talk with a friend at all. You can get a lot of the benefits of talking with a friend by talking with a duck, and without taking up another person’s time.

Even though I use this technique so often, I’m still so surprised every time it helps. It really does.

Writing

Writing is the third tool in your toolbelt. Writing can help you go even deeper on an issue than just talking or thinking. Writing encourages you to use the most accurate terms. Writing activates a different part of the brain, and makes you really nail down thoughts and feelings.

You might start by writing out everything in a stream-of-consciousness way, “brainstorming” what thoughts and feelings you have going on. You can then re-read and edit it until it feels accurate. Some parts may feel “off”, and you can iterate on the wording of these parts. Try to use the most specific words you can, especially for emotions.

I use the term “journaling” to mean “writing out thoughts and feelings”, wherever and whenever that is. This is useful even if you don’t write those thoughts and feelings in a notebook every day before bed.

You don’t need a physical journal to practice journaling. Some people prefer digital journaling using a computer or phone. My favorite place to journal is in an email draft message. It is quick to load and doesn’t have any frills to get in the way. Often I’ll start an email draft imagining I would send it to a coworker (but with my name in the “to:” to be safe).

You can write to yourself, future-you, past-you, or to the journal itself. You could write to your rubber duck, your best friend, or anyone.

Meditation

Practicing meditation can help you become more aware of your thoughts and emotions. Unlike many of the other techniques, meditation is not great for actively thinking about and processing experiences. It is useful for becoming aware of thoughts and feelings in the first place and accepting them as inputs, so that you can process them later.

If you’d like to try getting into meditation, there are a lot of resources to help you get started in a gentle and gradual way. My favorite introduction to meditation is a mobile app “Headspace”. It introduces meditation concepts one at a time, using voice guidance and cute little video animations.

Rumination is a risk with meditation. Sitting with these normally-unseen thoughts and feelings can be stressful. Stress is more likely to happen when in a particularly challenging situation, or when mentally or bodily fatigued. It is easy to judge these and accidentally kick off a downward spiral, making yourself feel worse. This risk is especially high for beginners. With practice, you will get better at not judging your thoughts and feelings.

Reading fiction

Some people believe that nonfiction reading is more useful than fiction reading. Nonfiction books teach us facts. But both are useful in their own way. Nonfiction books may teach facts, but fiction books are useful for social and emotional development.

Fiction books give you the opportunity to peer inside another person’s mind. You get to see how the characters interact with others and the results of those interactions. The characters often act in ways we wouldn’t ourselves, and in situations we could never find ourselves in. Even in similar situtaions, a character’s thoughts and feelings are often quite different from how you yourself would react in that situation. Reading fiction helps you imagine ways other people think.

The only way an author is able to convey these thoughts and feelings is to use words. If you can pick up on their wording or vocabulary that can help with your own wording and vocabulary.

Some research has been done on this phenomenon, using the “narrative transportation theory”. The term “high emotional transportation” means a story where the reader imagines they are immersed in the world, empathizing with the characters more deeply. Some studies show that people who have recently read “high emotional transportation” books have greater empathy than those who read something without high emotional transportation.

Try reading some fiction! You don’t need to read from a high school English class curriculum; today’s popular fiction totally counts. If you need an idea, maybe start with something from the top 10 bestsellers list for this year. You probably even know some people who have read one of those, and you can bond over that.

Emotional vocabulary

Children are usually taught the most simple emotions first — like happy, sad, angry, tired — and later they learn how to describe more complex emotions. You understand many more words than you regularly use, and this applies to emotional vocabulary as well. With practice, you can learn to wield a much richer emotional vocabulary.

Enriching your vocabulary can help you with both automatic and deliberate thoughts/feelings. The more you deliberately think using richer vocabulary, the more your automatic thoughts will use them as well. Nudging your automatic thoughts in this direction can substantially change the way you process experiences. The line between automatic and deliberate thoughts can be blurry, and that’s normal.

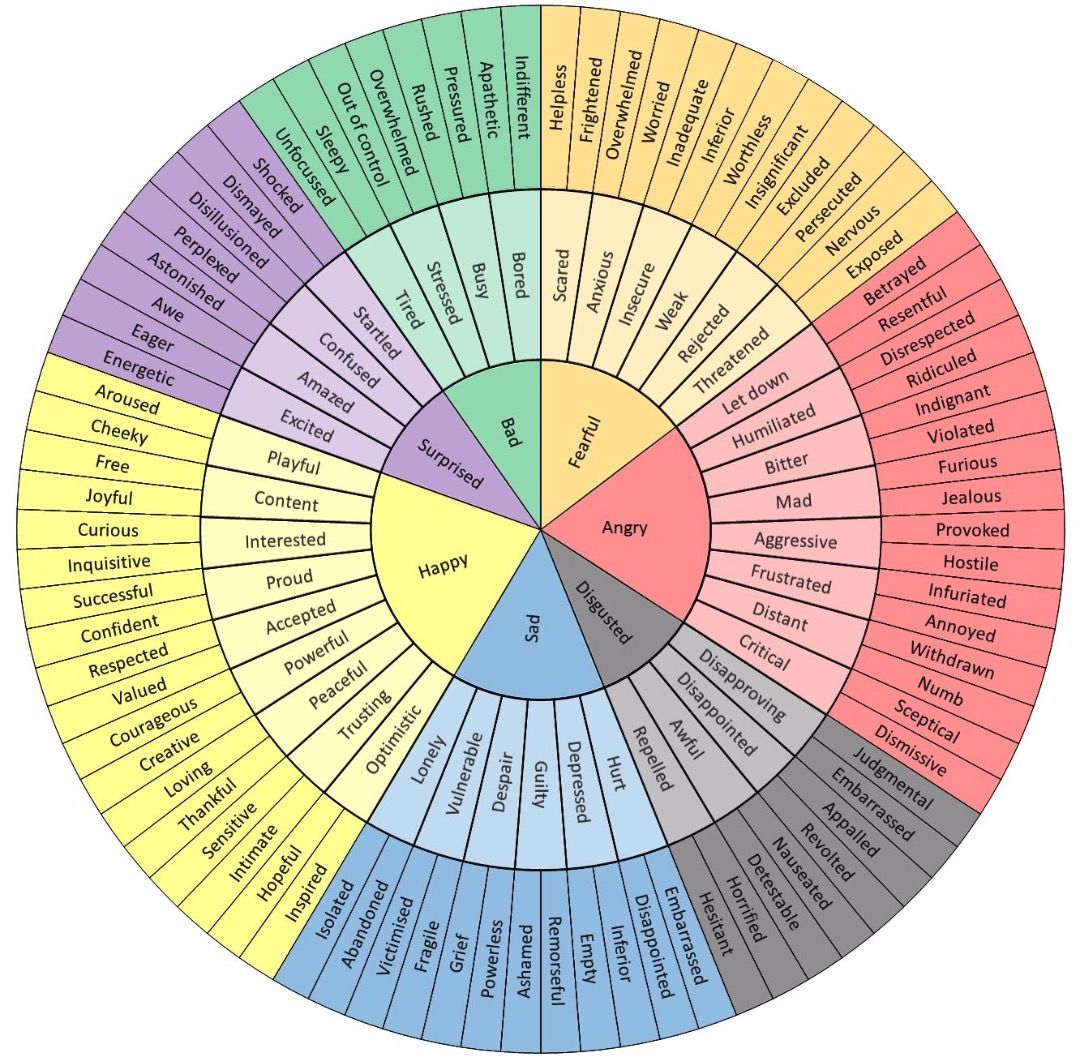

You can use an emotion thesaurus chart to expand your emotional vocabulary. Keep a reference like this one somewhere handy; print this one out, or save it to your desktop. There are many more resources like this online - some in circular graphs, some with more colors.

Feelings Wheel by Dr. Gloria Wilcox

Feelings Wheel by Dr. Gloria Wilcox

The next time you are trying to describe your emotions, whether to yourself or to someone else, try using the reference. You may find a word a little more accurate than what you would think of naturally. You might also try a traditional thesaurus, or ask a friend how they would describe it.

Homework

- Print out the emotional vocabulary chart from this article, to have it handy next time you need it. If you can’t print it, make it accessible somehow: save it to your desktop or email it to yourself and star it.

- Look for others to print, too - there are a lot of these available.

- Try processing emotions a bit each day this week. Try a different tactic each day this week:

- Schedule a time with a friend to talk about your feelings

- Discuss a problem with a “rubber duck” for 10 minutes

- Journal for 10 minutes once

- Meditate (at least 3 sessions). Perhaps using the Headspace app for guidance.

- Read more about the Six Levels of Validation

- This high-level overview article

- Or this original source (download pdf) from “Validation and Psychotherapy” by Marsha Linehan, 1997.

- Choose a fiction book to read. An audiobook counts just as well.

Read More

“Debugging Your Brain” is a 5-part series.

- ”Part 1: Modeling” - When brain-debugging helps, and a model of how the brain works when debugging.

- ”Part 2: Breakpoints” - How to get your mind into a state where you can debug: how to hit a breakpoint. Here you’ll investigate what the “inputs” to your system are.

- ”Part 3: Processing Experiences” - Six concrete ways to deal with processing experiences more fully and effectively.

- ”Part 4: Validation and Close Relationships” - How to effectively validate and support close friends.

- ”Part 5: Thoughts” - You’ll learn about the 10 most common “maladaptive thought patterns” you’ll want to look out for and convert into “adaptive” thought patterns.